Understanding Guitar Voicing - How Builders Shape Tone

What Voicing Really Means

In the circles of the luthiery world, one might often hear the mention of voicing. It sounds mysterious, secretive, and sometimes downright proprietary. In a sense, it is all of the above — but without it, building a great‑sounding guitar becomes a hit‑or‑miss proposition. There are many builders and manufacturers who take a cookie‑cutter approach to the voice of the instrument: a standardized brace set, a standard top thickness, glue it together, and hope for the best. Often this is done without a real understanding of, or concern for, the final tonal result.

Voicing is paramount to achieving the “sound” profile of a guitar, or any other luthier‑built instrument. It involves the calculated removal of wood — and sometimes the addition of it — to achieve a tonal character and responsiveness that elevate an instrument from ordinary to exceptional. Voicing sets the vibrational mobility of the top, working in concert with the back, to create a balanced tonal spectrum, a controlled overtone structure, appropriate projection, and a responsiveness tailored to the player’s style. In the realm of fine custom instruments, this is where the instrument becomes personal.

Voicing is also deeply individualistic, both in procedure and in results. If you ask ten luthiers to explain their voicing techniques in detail, you will likely get eight to ten different approaches to achieving their particular sound. That does not mean any one method is incorrect. Each builder who truly voices an instrument develops their own style, and as a result, their own “voice.”

The Guitar as a Responsive System

When you look at the physics of how a stringed instrument works, it ultimately comes down to a simple chain of events. Whether the instrument is plucked or bowed, the strings vibrate and transfer that energy into the top. The top responds by forming complex vibrational patterns, which in turn excite the air column inside the body. That internal air movement activates the back, and together the top, air, and back project what we perceive as sound. How easily the instrument can carry out this chain of events is what we refer to as its responsiveness. In its simplest form, a stringed instrument is essentially an air pump — and it is the builder’s responsibility to make it an effective and tonally pleasing one.

The prospects of achieving this begin with the top of the guitar. While the strings

This is where the typical factory‑built guitar diverges from a fine handcrafted instrument. In a factory setting, builders know that most of their guitars will be played with a pick, that string tension introduces structural risk, and that ever‑changing temperature and humidity conditions can wreak havoc on lightly built instruments. As a result, they lean heavily toward the overbuilt side of the spectrum. Why? The answer is simple: warranty work. They want to avoid it — and who could blame them? It’s a profit killer.

Another aspect of the factory‑built guitar is that two instruments with identical specifications will often have noticeably different tonal qualities, responsiveness, and overall character. That is simply the nature of the materials. Wood varies, even within the same species, and a standardized, assembly‑line approach cannot account for those differences.

A luthier, however, can shape the tone and responsiveness of an instrument to specific preferences. He is concerned not just with thickness, but with stiffness — how the material actually behaves under tension. He has the opportunity to devote time and attention to the touch, feel, and tap of the plates and braces. A knowledgeable builder can guide the instrument toward a desired tonal outcome, shaping both its voice and its responsiveness in ways mass production cannot achieve.

A simple understanding of what responsiveness means is warranted. Responsiveness can be defined as how much or how little string activation is required to produce sound, and how quickly that sound develops. Is the guitar fast‑acting or slow to respond? Does it project easily, or does the sound feel contained? All of this falls into the hands of the luthier when the endeavor of voicing takes place.

The Goals of Voicing

It would be an obvious understatement to say that the goal of voicing is simply to achieve a good‑sounding instrument. While that is certainly part of the equation, there are several deeper considerations involved in reaching that goal. A good‑sounding guitar will have balance, projection, and responsiveness — all of the qualities we’ve already discussed. However, a luthier who cares about his craft at the right level is not aiming for a good instrument. He is aiming for a great one.

When “great” is the goal, there are checks and balances that must be respected. The back and top must have the proper separation in their tonal responses to avoid the dreaded wolf notes. If you have ever experienced one, you know the havoc they can wreak.

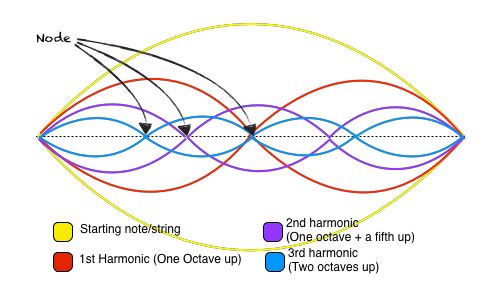

The builder is also concerned with shaping the vibrational nodes to produce clear harmonics, commonly referred to as overtones. This requires a careful balancing act: overtones should be present and pleasing, not overpowering or muddy. While certain materials can enhance overtone content, every instrument has the potential to produce them. Through voicing, the luthier can draw them out to the right degree.

All aspects of voicing require the ability to listen and discern what changes should be made to bring out the greatest amount of musicality from the materials at hand — and to understand the consequences of those changes. A finely built and voiced guitar is constructed light enough to produce the best sound possible, yet strong enough to remain structurally sound. In many ways, it is an instrument that teeters on the edge of disaster, with just enough weight on the safe side of the scale to keep everything intact.

Wood Characteristics and Their Influence

Wood is a plentiful resource. It is used in various forms of construction because of its strength properties and relative cost when compared to alternative. With that stated it must also be noted that not all wood, regardless of how plentiful it is or is not, is suitable for the construction of a stringed instrument. Factors such as density, stiffness, grain structure, and specific cut are all elements that must be examined. One would not typically employ a wood with the characteristic of oak to the construction of a guitar top, just as one would not consider balsa wood for either a top or back and side sets. Proper wood choices must be made, and whether consciously or sub-consciously those decisions impact the choices of voicing to a significant degree.

Typically speaking, most builders want a top with a good stiffness to weight ratio. Hence, selections such as various spruces and cedar or popular choices. The luthier that concerns himself with voicing will desire to bring those properties into a known standard, not of thickness, but rather stiffness, by performing deflection testing. The same thing is true with the choices involving with bracing material. This approach departs greatly from the standardized thickness and brace sizing of the factory instrument.

An educated and aware luthier will understand that there is also a variance within the same species of wood. It is possible to take 2 pieces of wood cut from the same billet, dimension them identically, and see two different stiffness and weights between the two pieces. So care and attention is given at the outset of a build, whether realized or not, toward the future sound of the guitar, or its “voice.”

Overtones were touched on briefly in the preceding section. The voice‑aware luthier understands more than weight and stiffness; he also considers the reflective qualities of the wood, which play a significant role in overtone production. For example, guitars constructed of mahogany or maple tend to be somewhat “drier” in tone — a term that simply means the overtones are less pronounced. Evidence of this principle can be observed through the art of tapping. If one taps a plate of mahogany, it will often produce more of a thud when compared to Brazilian rosewood or many other Dalbergia species. Density, stiffness, and weight all play their part. Choices in how the back is handled influence the voice long before the first chisel is taken to the bracing structure

What Do Players Hear?

It is an undisputed fact that sound and tone are subjective. What one player finds perfect, another may find lacking. What one considers the golden standard, another may view as sub‑standard. Just as beauty is in the eye of the beholder, tone is in the ear of the hearer. This is not to say that one is right and the other wrong; it simply frames the individualistic nature of tone, sound, and what voicing brings into the equation.

When I build a guitar for my own enjoyment, or on pure speculation, I naturally lean toward my personal playing style and tonal preferences. That can change quickly when building for a client.

At the outset, I try to gain an understanding of what a player likes from a tonal perspective. I want to know what their playing style encompasses. Do they appreciate overtones that create an incredibly round, lush sound? Or do they play more melodic phrases that require overtones to be slightly restrained so notes do not run together, allowing tonal separation to remain clear and intentional?

These factors determine the choices a builder must work through to match the instrument — as closely as understanding will allow — to the player’s ear. They help form a guideline for the resonant frequency and responsiveness the luthier must aim for when the work of voicing begins.With this in mind, I find it futile to describe what “good tone” or “great voicing” means for everyone. My advice to anyone seeking a custom‑built guitar is simple: talk to builders, gain a sense of their voicing philosophies, listen to their guidance on material selection, and make informed decisions. Even then, the individualistic variable of tone remains.

What exactly do I mean? I am of the contention that many players would struggle in a blindfolded test to discern whether a guitar has a Swiss spruce top or an Engelmann spruce top, or whether the back is $3,000 Brazilian rosewood or $1,000 Cocobolo. This is why I tend to chuckle when someone says, “That sounds like Brazilian,” or any other species. Why? Because the voice of a guitar is not limited to the species — it rests far more heavily in the hands of the luthier.

Why Is Voicing the Signature of an Experienced Luthier?

A more accurate way to pose this question might be: what makes the voicing of one builder such a defining aspect of their craft? The answer is simple on the surface, yet deeply complex at its core.

Consider it this way: why doesn’t everyone play a Martin, a Taylor, or a Gibson? Why do players of fine, luthier‑built instruments gravitate toward a wide variety of individual builders—especially those who devote the necessary attention to the art of voicing?

Any builder who has gone through the gauntlet of learning and experience has produced instruments that were, by their own admission, duds. They have also produced instruments that were phenomenal. And without a doubt, they have produced many that fall at every point in between. The struggle for consistency is real.

Voicing‑minded luthiers have, without question, formed a tonal vision in their mind that they seek to achieve. In pursuit of that vision, they have recorded each step, tested countless combinations of stiffness and weight, tapped thousands of top and back plates, felt the wood in their hands, and made decisions that were sometimes for the better and sometimes for the worse. In a nutshell, voicing— as mentioned earlier—doesn’t begin when the chisel touches the bracing. It begins in the earliest stages of the build, drawing from years of experience devoted to learning the craft and developing one’s voice.

Many well‑known luthiers have developed strategies, intuition, and a deep understanding of how to manipulate materials to achieve a tonally pleasing sound. And they hold much of that information as proprietary. How much should a top deflect under a specific weight? For one builder the answer will be value A, for another value B, and for yet another value C. How did they arrive at their values? Through individual experience and the testing of various metrics across many builds.

I have what works for me. I have my own philosophy—developed and continually refined through every instrument I build. It is part of a personal journey to find that expressed sound. Voicing turns the luthier into a tone chaser, always striving for that golden sound, that perfect responsiveness, that balanced spectrum that is pleasing to themselves first, and hopefully to the audience they seek to reach.

Have I been successful? To some, yes. To others, no. But my journey in voicing and tone chasing has afforded me the opportunity to build guitars for a wide audience all over the world. It has given me the privilege of building for Tommy Emmanuel, and no fewer than five instruments for Muriel Anderson. And yet, I will quickly say that I have not arrived. I am still a student of shaping tone and responsiveness, and I remain committed to a personal pursuit of continual improvement in the art of voicing.